At Elevate, we know that identifying and securing grants is often the backbone of nonprofit funding strategies. We also realize that finding the right funders and crafting compelling proposals requires more than just a surface-level search—it demands strategic and comprehensive prospect research. Using multiple research tools is not just recommended; it’s essential for maximizing your grant success. Here’s why and how to do it effectively.

Why Use Multiple Prospect Research Tools?

Grantmakers often don’t reveal their full scope of funding interests on their websites. For example, a glance at the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation’s website might lead you to believe they only offer scholarships to Nebraska students. However, digging deeper with tools like Candid’s Foundation Directory Online (FDO) or Inside Philanthropy reveals their significant contributions to reproductive health initiatives. This deeper understanding can help nonprofits determine strategic alignment and customize proposals accordingly.

Elevate’s Toolbox for Comprehensive Prospect Research

At Elevate, leveraging a mix of paid and free prospect research tools ensures high-quality outcomes for clients. Here’s a breakdown of some key tools and how they can elevate your grant-seeking efforts:

At Elevate, leveraging a mix of paid and free prospect research tools ensures high-quality outcomes for clients. Here’s a breakdown of some key tools and how they can elevate your grant-seeking efforts:

1. Salesforce (or your own donor database)

- What It Does: Tracks funder and opportunity records with comprehensive data, including email history and activity logs.

- Why It’s Unique: Elevate’s extensive internal database allows teams to analyze trends across thousands of funders. Collaboration is seamless, as team members can share insights and follow up on opportunities.

2. Candid (FDO)

- What It Does: Provides profiles on nearly 300,000 grantmakers and 2 million grant recipients, along with 990 forms, grant opportunities, and federal grant information.

- Why It’s Unique: Its LinkedIn integration and ability to export data to Excel make it a powerful tool for strategy analysis and networking.

3. Inside Philanthropy

3. Inside Philanthropy

- What It Does: Features profiles of grantmaking organizations and tracks open RFPs with its GrantFinder tool.

- Why It’s Unique: Users can filter funders by issue, geography, and major donors while accessing articles on philanthropy trends.

4. Instrumentl

- What It Does: Generates comprehensive “funding landscapes” that highlight relevant funders and open opportunities in specific sectors.

- Why It’s Unique: Its “openness to new grantees” insights and high-volume prospect generation set it apart.

5. Free Tools (e.g., LinkedIn, CauseIQ, and Influence Watch)

- What They Do: Provide access to information on influencers, funders, and peer organizations. Tools like LinkedIn help build connections with program officers and grantmakers.

- Why They’re Valuable: Free resources often complement paid tools by filling in gaps or providing quick, high-level insights.

Best Practices for Effective Prospect Research

- Start with a Strategic Plan: Identify your funding priorities and narrow your search to tools and resources that align with your organization’s mission.

- Combine Tools for Deeper Insights: Cross-reference information from multiple sources to uncover hidden opportunities and verify funder alignment.

- Stay Organized: Log your findings, track communication history, and collaborate with your team.

- Stay Current: Regularly review platforms like Inside Philanthropy and the Chronicle of Philanthropy for updates on grantmaking trends.

- Engage with Funders: Use LinkedIn or email to connect with program officers, build relationships, and gain insight into funder priorities.

Conclusion

In today’s competitive funding landscape, successful grant seeking requires more than just a quick Google search. By utilizing multiple prospect research tools, nonprofits can uncover opportunities that align with their mission, craft tailored proposals, and build lasting relationships with funders. With a well-rounded approach to research, your organization can maximize its chances of securing the grants it needs to thrive.

And for more on prospecting, join us for Elevate’s popular Prospect Research: How to Find Grant Opportunities webinar.

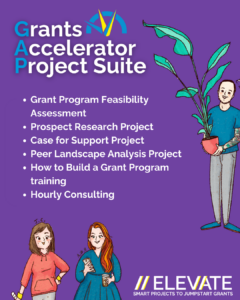

New year, new grant services–that’s the saying right? Either way, I am very excited for the opportunity to share more information about the launch of Elevate’s newest services: the Grants Accelerator Project Suite. These projects are designed to take the strategic grant work that Elevate is known for and package it into bite size pieces that are perfect for organizations that are just getting their grant programs started. Read on to learn more about Elevate’s new offerings and how you can move forward if they sound right for you.

If you’ve been in Elevate’s orbit for a while, this name may sound familiar–for the last several years we have offered a three- or four-month Grants Accelerator Project that brought together grants strategy guidance, prospecting, and language generation. We’ve worked with dozens of organizations on these projects, helping to stand up new grant programs and set organizations on the path to grant sustainability. However, we recognized that this package wasn’t quite right for organizations that were really trying to figure out how to get started from square one, and that the bundling of multiple types of support could lead us to inadvertently miss the mark on what an organization really needed. So, in 2024 we decided to deconstruct the Grants Accelerator Project into its component parts (and add a few new projects!) to create the Grants Accelerator Project Suite!

Through the new GAP Suite, we’re excited to offer a menu of project-based engagements that are cost efficient, maintain a laser focus on a specific component of an effective grants program, and are modular in order to build on each other in the way that makes the most sense for each organization. Each project within the GAP Suite is a four- or six-week collaboration designed to address a specific strategic fundraising need or question. While we have a standard sequence that many organizations will fit into, we can build out a series of engagements that best fits your needs and resources on a timeline that works for you.

Through the new GAP Suite, we’re excited to offer a menu of project-based engagements that are cost efficient, maintain a laser focus on a specific component of an effective grants program, and are modular in order to build on each other in the way that makes the most sense for each organization. Each project within the GAP Suite is a four- or six-week collaboration designed to address a specific strategic fundraising need or question. While we have a standard sequence that many organizations will fit into, we can build out a series of engagements that best fits your needs and resources on a timeline that works for you.

We’ve built these projects for small organizations that are at the beginning of their grant journey as well as for those that are interested in launching a new initiative or program that would require new dedicated grant funding. They are perfect if you are looking for guidance on how to get started with grants or need to figure out how to convert your initial seed funds into a more sustainable pipeline. Because we know that it can be difficult to commit to a long-term engagement, these projects are intentionally short and highly focused. At the end of each project, we’ll discuss what your next steps could look like within the GAP suite or within your organization.

If you’re interested in learning more about these new options, check out the GAP Suite page on Elevate’s website. On that page, you’ll find more information about each of the different projects and instructions on how to get started. You’ll also find information on how to join an upcoming GAP info session where you can ask questions before you get started. We look forward to seeing you there!

If you’re a grant seeker, you’ve likely encountered these scenarios.

Scenario 1: You have an existing, positive relationship with a funder. You’ve submitted a proposal for an expanded or new initiative you thought would interest them, but you received a polite decline.

Scenario 2: You identified a perfect new funding prospect. You submitted an inaugural proposal after receiving the greenlight on an LOI, but ultimately the funder did not make an award.

We’ve all been there.

No one relishes hearing the word NO in response to a funding request. While sources vary, an estimated 80% of grant proposals are declined, so any grantseeker is bound to experience their share of rejections. But when you consider – as in all things in life! – that timing is everything, a “No” doesn’t have to remain a “No” for all time. It might help to think of “No” as “Not right now.”

To that end, the team at Elevate pulled together a few of our tried-and-true tips to help you convert a funder NO into a future YES.

1. Open yourself to feedback.

There are many factors that go into funding decisions, both subjective and objective. While you believe in your mission and your organization does excellent work, don’t let that stand in the way of seeing how you can get another bite at the apple. Treat the declination as a valuable learning experience.

There are many factors that go into funding decisions, both subjective and objective. While you believe in your mission and your organization does excellent work, don’t let that stand in the way of seeing how you can get another bite at the apple. Treat the declination as a valuable learning experience.

In addition to graciously thanking the funder for their consideration, invest the time in asking what you could do differently to increase your chances of securing the grant in the next cycle.

If a funder shares any questions or concerns that arose from the proposal, use these inputs to help you shore up those elements for the next grant cycle, make your proposal more compelling, or strengthen an appeal to a different funder who may be interested in your project.

Additionally, in the case of funders that you have not been able to cultivate prior to a request, your first grant proposal might simply be your opportunity to introduce yourself. Consider that even if a proposal was declined, if it opened the door for you to develop a relationship with a new funder, it was by no means a waste of time or effort. Use any communication as an opportunity to reiterate your alignment with the funder’s interests and ask for feedback and an opportunity to apply again in the future.

2. Request a follow-up conversation.

Not all program officers have the time or capacity to hold follow-up conversations about a declined proposal, but many do! Unless they explicitly state otherwise, you should absolutely take the opportunity to request feedback from the funder about your proposal. Request a phone call or meeting, and ask them how you may position yourself to be a more competitive applicant next time around. You can also gauge their interest in other facets of your programming in case something your organization does interests them more than what you originally proposed.

Not all program officers have the time or capacity to hold follow-up conversations about a declined proposal, but many do! Unless they explicitly state otherwise, you should absolutely take the opportunity to request feedback from the funder about your proposal. Request a phone call or meeting, and ask them how you may position yourself to be a more competitive applicant next time around. You can also gauge their interest in other facets of your programming in case something your organization does interests them more than what you originally proposed.

A meeting with a foundation program officer or Board member is a chance to get some behind-the-scenes information. For example, one Elevate team’s client was ostensibly within the funder’s geographic footprint based on eligibility criteria. However, upon speaking to the program officer, our client learned that the foundation had yet to ramp up their giving in the specific neighborhood where the organization is situated, and that they plan to do so the following year. With this encouraging news, the Elevate team planned to submit another request when the foundation was more likely to award a grant to our client.

Alternatively, if it’s challenging to get a meeting on the books, you could ask the funder via phone or email whether they would encourage your organization to reapply during the next grant cycle. Their response may end up yielding some useful insight about your likelihood of securing funding in the future.

3. Seek opportunities to expand your funder network.

For the most part, foundations operate within a landscape of like-minded organizations, just as nonprofits do. Many funders maintain networks of other philanthropic organizations that share aspects of their giving priorities, and they may even participate in an affinity group of foundations with shared interests. For this reason, after a foundation declines your proposal, it can be valuable to appeal to the funder’s expertise when it comes to other organizations that share their funding priorities. Ask them about other organizations or foundations that they think may be interested in your work, and don’t be afraid to request an introduction to a good point of contact.

For the most part, foundations operate within a landscape of like-minded organizations, just as nonprofits do. Many funders maintain networks of other philanthropic organizations that share aspects of their giving priorities, and they may even participate in an affinity group of foundations with shared interests. For this reason, after a foundation declines your proposal, it can be valuable to appeal to the funder’s expertise when it comes to other organizations that share their funding priorities. Ask them about other organizations or foundations that they think may be interested in your work, and don’t be afraid to request an introduction to a good point of contact.

4. Offer to keep the funder in the loop about your organization.

Fundraising is a long game, so it’s important to be persistent when building a relationship with a grantmaker. As part of your stewardship efforts, you might offer to send periodic updates about your organization’s work or seek to connect with a potential funder through a site visit or a networking event. As a result, they may better understand your work – and your alignment with their interests – the next time you request funding.

5. Refine your prospecting strategy.

Sometimes, a “No” truly is a “No.” If a program officer makes this explicit, it is not going to do you any good to persist—and may harm your organization’s reputation if you do!

Sometimes, a “No” truly is a “No.” If a program officer makes this explicit, it is not going to do you any good to persist—and may harm your organization’s reputation if you do!

However, this does not mean there isn’t something to learn from the scenario. Reflect on where you misunderstood your organization’s alignment with the funder’s interest, and use this to refine your prospecting strategy so that you can focus on grant opportunities that you are more likely to win.

Consider this example: A nonprofit organization focused on providing services to people who are unhoused submits a grant request to a funder with a broad priority of “housing security”. The request is declined, and after following up to ask for feedback from the program officer, the organization learns that this grantmaker invests in advocacy and systems change organizations rather than those providing direct services. With this information, the nonprofit refines its prospecting strategy to ensure that in the future it pursues grant opportunities with a clear interest in funding direct services.

The bottom line: In order to build a grant program, you are going to hear “No.” But do not despair! Your next steps will make all the difference when it comes to building relationships and refining your grantseeking strategy. And, sometimes you can make bad news work for you!

For more on how to make the most out of a declination, check out this article on Candid. Relatedly, see our blogs on “5 Reasons to Cultivate Relationships with Funders” and “5 Ways to be Pleasantly Persistent with Funder Cultivation.”

It is not uncommon for human services organizations to rely heavily on public funds – grants and contracts from local, state, or federal agencies. In fact, many would argue that this is the way it should be, that it is the responsibility of the government to fund housing efforts, health services, maternal healthcare, early childhood programs, arrest diversion, mental and behavioral health initiatives, and other programs that address the needs of vulnerable members of society.

So what does this mean for fundraising from private foundations in the field of human services?

Diversified revenues are crucial for just about any organization, creating sustainability and resilience when a funding source runs dry. While human services organizations may have a substantial public funding portfolio, and many government grants require a private funding match, this does not mean that other sources of revenue – including earned income and philanthropic funds – should take a back seat in your funding strategy. In fact, I encourage you to think differently about philanthropy and its role in supporting human services providers.

Diversified revenues are crucial for just about any organization, creating sustainability and resilience when a funding source runs dry. While human services organizations may have a substantial public funding portfolio, and many government grants require a private funding match, this does not mean that other sources of revenue – including earned income and philanthropic funds – should take a back seat in your funding strategy. In fact, I encourage you to think differently about philanthropy and its role in supporting human services providers.

Imagine you’re on the leadership team of a service provider that implements a highly effective program for returning citizens; clients successfully maintain housing and jobs, and avoid further justice-system involvement. A contract with the state Department of Justice makes up the majority of the program budget, with the balance coming from a Master Leasing initiative and one wealthy individual donor who gives annually. For the most part, the program is meeting the needs of the population it currently reaches, but there is zero capacity for expansion, innovation, or outreach.

The Board and leadership team is concerned with the long-term sustainability for the program, and next steps involve developing a strategy to diversify revenues for the organization. A discussion ensues around pursuing foundation grants as a key tactic for diversification. The leadership team considers which aspects of the program may be well-suited to private grant opportunities. Should you seek grant opportunities for direct program expenses like rent and food assistance? Or are foundations more likely to support a new outreach component focused on engaging those who are incarcerated before their release? Perhaps you should seek General Operating Support?

If invited to that debate, I would argue that public funds can and should be used for direct programmatic expenses,  whereas there may be a unique role for private foundations to provide the funding needed to build capacity, test new ideas, and establish the evidence for what works.

whereas there may be a unique role for private foundations to provide the funding needed to build capacity, test new ideas, and establish the evidence for what works.

My advice to the leadership and development teams at human services organizations: Do not primarily think of private foundation grants and other philanthropic contributions as a budget gap-filler. Consider where public funds can and should be used, and where private philanthropy can have a unique impact.

For example, social services organizations might focus philanthropic asks on:

- Well thought-out new initiatives for which you need to establish proof of concept before advocating for public investment;

- Support for concrete diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives;

- Organizational capacity building (investments in a strategic plan, executive coach, or development strategist, for example);

- Initiatives that are crucial to your clients’ wellbeing where public funders limit their support (such as access to abortion services, gender-affirming care, or harm-reduction initiatives); and

- General Operating Support!

Above all, the grant request most likely to be funded is the one that is aligned with the foundation’s own priorities, adheres to its proposal guidelines, and for which you have the encouragement of foundation program officers, Board members, or other decision makers to apply.

Above all, the grant request most likely to be funded is the one that is aligned with the foundation’s own priorities, adheres to its proposal guidelines, and for which you have the encouragement of foundation program officers, Board members, or other decision makers to apply.

Is your organization ready to establish (or grow) a private grants program? The team at Elevate can help! Reach out to us at hello@elevatedeffect.com to learn more about our work with nonprofits throughout the U.S. to build smart and strategic grants programs.

A version of this article was originally published in the Summer 2023 edition of The Provider Newspaper, the flagship publication of the Providers’ Council.

November 6, 2019

Elevate is proud to share that several of our team members were selected to present three different breakout sessions at the Grant Professionals Association Annual Conference, which was held November 6-9, 2019 in Washington, DC!

Leading up to the conference, we’re sharing previews of these sessions, and some of what our presenters will be teaching. In this post, we’re looking at what it takes to put together a smart, strategic prospect research strategy for your organization.

Developing a clear prospecting strategy and organizing your prospect research to identify the best-aligned foundation and corporate leads for your organization is critical to the success of any prospecting effort.

No matter how robust your organization’s grants program may be, nonprofit leaders are often in a position where they need to identify and pursue new sources of funding. And since no organization can (or should!) pursue every possible funding opportunity that comes along, having a thoughtful strategy in place to help guide prospect research is essential so that we spend our time researching, identifying, and pursuing high-quality prospects.

So how does one build a prospecting strategy? Below we’ve outlined a few steps to help you create or refine your plans.

1. Create an ideal prospect profile

The first step is to get crystal clear on what a good prospect looks like for your needs. We find that our clients often want to pursue new prospects, but don’t yet have a clear vision within their organization of what a well-aligned prospect actually looks like for the work they do. In our experience, an “ideal prospect” should share an interest in the audience you serve, the geographic reach of your organization, the needs of the community, and the type of support you need, to name just a few.

In building your list of these points of alignment, you’ll want to ask yourself both, “What do we have to offer a funder?” as well as, “What do we want/need most from a funder?”

While creating your “ideal prospect” profile, you’ll also want to consider what are the deal breakers for your organization. For example, many organizations have policies that ensure that any partners they engage with align on key values. Small organizations may not have the capacity for very robust data tracking that some funders require. What are those factors that might lead your organization to decline funding? You’ll want to do your due diligence in the prospecting phase in order to avoid a lot of wasted effort later in the process!

2. identify and prioritize your search criteria

Using the “ideal prospect” profile you put together in step 1, you should then start to identify the criteria you’ll use to search for potential funders, and organize your internal research process based on your priorities. The greater the number of points of alignment you have with a funding prospect, the higher the probability that this prospect will be interested in supporting the organization’s work.

3. Assess the competitive landscape

Once you’ve gotten clearer about what you’re looking for in a funding prospect, this is a great time to do a little research into your peers and competitors to better understand the field in which you are competing for resources. Who is funding your peers? For what projects? At what grant amount? Some of these organizations are going to be your best prospects, as well. (And remember, it is rare for a foundation to only award one or two grants per cycle, so if you are successful in going after a peer organization’s funder, you are not necessarily taking resources that would have otherwise been designated for the other organization!)

—

Once you’ve tackled these three steps, we recommend you also consider focusing on getting information and buy-in from your internal stakeholders – such as the organization’s leaders and program staff – to develop your strategy. Include them in this process! This could start with something as simple as developing a clear and concise summary of your prospecting strategy and sharing it internally for feedback.

Ultimately you will want to develop a process for identifying and qualifying prospects to ensure that you are pursuing the most strategic, actionable opportunities possible. Think quality over quantity! If you are successful in developing and executing an effective prospect research strategy, you’ll be well-positioned to spend your limited time going after those prospects that are the most likely to be interested in funding your work.

Written by Caroline O’Shea and Jennifer O’Brien

Photo courtesy of wocintechchat.com

At Elevate, leveraging a mix of paid and free prospect research tools ensures high-quality outcomes for clients. Here’s a breakdown of some key tools and how they can elevate your grant-seeking efforts:

At Elevate, leveraging a mix of paid and free prospect research tools ensures high-quality outcomes for clients. Here’s a breakdown of some key tools and how they can elevate your grant-seeking efforts: 3. Inside Philanthropy

3. Inside Philanthropy Through the new GAP Suite, we’re excited to offer a menu of project-based engagements that are cost efficient, maintain a laser focus on a specific component of an effective grants program, and are modular in order to build on each other in the way that makes the most sense for each organization. Each project within the GAP Suite is a four- or six-week collaboration designed to address a specific strategic fundraising need or question. While we have a standard sequence that many organizations will fit into, we can build out a series of engagements that best fits your needs and resources on a timeline that works for you.

Through the new GAP Suite, we’re excited to offer a menu of project-based engagements that are cost efficient, maintain a laser focus on a specific component of an effective grants program, and are modular in order to build on each other in the way that makes the most sense for each organization. Each project within the GAP Suite is a four- or six-week collaboration designed to address a specific strategic fundraising need or question. While we have a standard sequence that many organizations will fit into, we can build out a series of engagements that best fits your needs and resources on a timeline that works for you.  There are many factors that go into funding decisions, both subjective and objective. While you believe in your mission and your organization does excellent work, don’t let that stand in the way of seeing how you can get another bite at the apple. Treat the declination as a valuable learning experience.

There are many factors that go into funding decisions, both subjective and objective. While you believe in your mission and your organization does excellent work, don’t let that stand in the way of seeing how you can get another bite at the apple. Treat the declination as a valuable learning experience.  Not all program officers have the time or capacity to hold follow-up conversations about a declined proposal, but many do! Unless they explicitly state otherwise, you should absolutely take the opportunity to request feedback from the funder about your proposal. Request a phone call or meeting, and ask them how you may position yourself to be a more competitive applicant next time around. You can also gauge their interest in other facets of your programming in case something your organization does interests them more than what you originally proposed.

Not all program officers have the time or capacity to hold follow-up conversations about a declined proposal, but many do! Unless they explicitly state otherwise, you should absolutely take the opportunity to request feedback from the funder about your proposal. Request a phone call or meeting, and ask them how you may position yourself to be a more competitive applicant next time around. You can also gauge their interest in other facets of your programming in case something your organization does interests them more than what you originally proposed.  For the most part, foundations operate within a landscape of like-minded organizations, just as nonprofits do. Many funders maintain networks of other philanthropic organizations that share aspects of their giving priorities, and they may even participate in an

For the most part, foundations operate within a landscape of like-minded organizations, just as nonprofits do. Many funders maintain networks of other philanthropic organizations that share aspects of their giving priorities, and they may even participate in an  Sometimes, a “No” truly is a “No.” If a program officer makes this explicit, it is not going to do you any good to persist—and may harm your organization’s reputation if you do!

Sometimes, a “No” truly is a “No.” If a program officer makes this explicit, it is not going to do you any good to persist—and may harm your organization’s reputation if you do! Diversified revenues are crucial for just about any organization, creating sustainability and resilience when a funding source runs dry.

Diversified revenues are crucial for just about any organization, creating sustainability and resilience when a funding source runs dry. whereas

whereas  Above all, the grant request most likely to be funded is the one that is aligned with the foundation’s own priorities, adheres to its proposal guidelines, and for which you have the encouragement of foundation program officers, Board members, or other decision makers to apply.

Above all, the grant request most likely to be funded is the one that is aligned with the foundation’s own priorities, adheres to its proposal guidelines, and for which you have the encouragement of foundation program officers, Board members, or other decision makers to apply.