Previously in this space, I shared some facets of my personal equity journey, which has included learning about human-centered design, and participating in a training workshop with the National Equity Project (NEP) on how this design process can be applied to address both internal and external organizational equity challenges. Specifically, I introduced the NEP’s Liberatory Design model, which is an approach to address equity challenges and change efforts in complex systems.

The Liberatory Design Model is a process and practice to:

- Create designs that help interrupt inequity and increase opportunity for those most impacted by oppression;

- Transform power by shifting the relationships between those who hold power to design and those impacted by these designs; and

- Generate critical learning and increased agency for those involved in the design work.

To better enhance my understanding of the applications and practice of LIberatory Design, I sat down with the NEP’s Tom Malarkey.

Tom is a Director with the National Equity Project, a non-profit based in Oakland and focused on equity-centered change work in public school systems and other youth-serving organizations. He is a facilitator, presenter, and coach supporting leadership development around racial equity, team development, and complex systems change and a lead developer of the NEP’s Liberatory Design and Learning Partnerships services. Tom has been with the NEP since 1996. Prior to that he taught high school English and first grade, and directed the Summerbridge program, a national model for academic empowerment and young teacher development. Tom holds an M.A. in international development education from Stanford University, and did doctoral work in Education at UC Berkeley. He has published several articles and book chapters on working towards equity in education.

Johnisha Levi: What are the origins of Liberatory Design?

Tom Malarkey: National Equity Project got onto design thinking and human-centered design about 12 years ago. We could immediately see the relevance and the connections to building equity. I specifically mean the importance of centering the folks that you are serving, doing deep and humanizing listening work, and bringing a sense of creativity into equity work — since equity work can be heavy, fraught, and complex, and it doesn’t always get you where you’re hoping to go.

We began incorporating aspects of human-centered design into our work. We wanted to do more, but we weren’t designers. We had a relationship with several people at Stanford University’s Design Program (the d.school’s K-12 Lab) – Susie Wise, David Clifford, and Tania Anaissie. They were sitting in a white dominant culture in Silicon Valley, and they saw that the way design thinking often manifested in the world was very oriented towards white dominant cultural norms. So they wanted to strengthen the equity dimension of their work. We both felt we needed to go beyond our own boundaries, so we started talking. We realized that we brought complementary strengths – and also complementary needs — and that something was possible here.

We began incorporating aspects of human-centered design into our work. We wanted to do more, but we weren’t designers. We had a relationship with several people at Stanford University’s Design Program (the d.school’s K-12 Lab) – Susie Wise, David Clifford, and Tania Anaissie. They were sitting in a white dominant culture in Silicon Valley, and they saw that the way design thinking often manifested in the world was very oriented towards white dominant cultural norms. So they wanted to strengthen the equity dimension of their work. We both felt we needed to go beyond our own boundaries, so we started talking. We realized that we brought complementary strengths – and also complementary needs — and that something was possible here.

We could feel there was a lot of synchronicity, and that, in the spirit of design, we needed to be making something together. Over time, we came to this idea of creating an equity- and complexity-centered version of design thinking that was grounded in the NEP’s Leading for Equity Framework and began prototyping a set of cards.

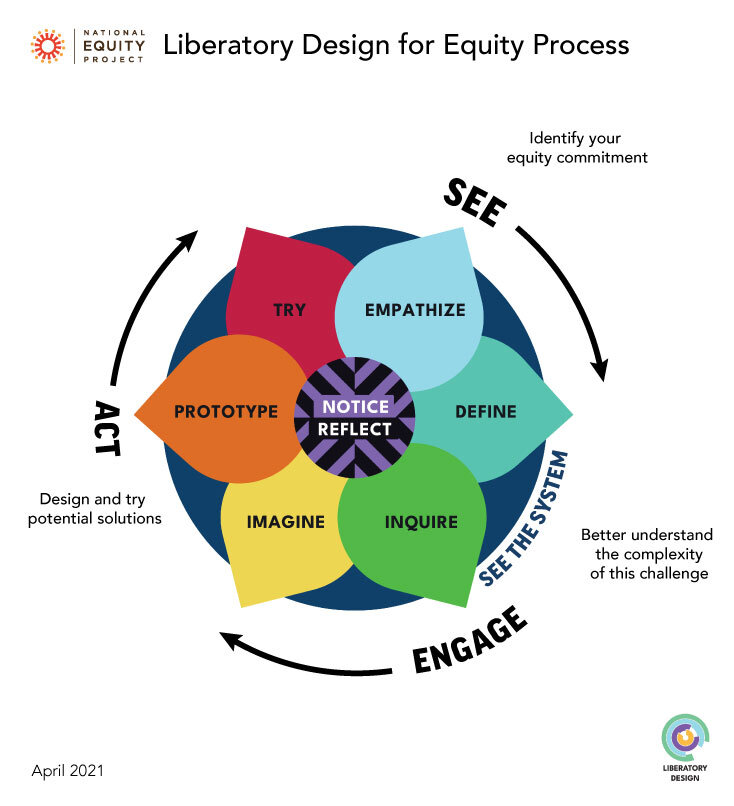

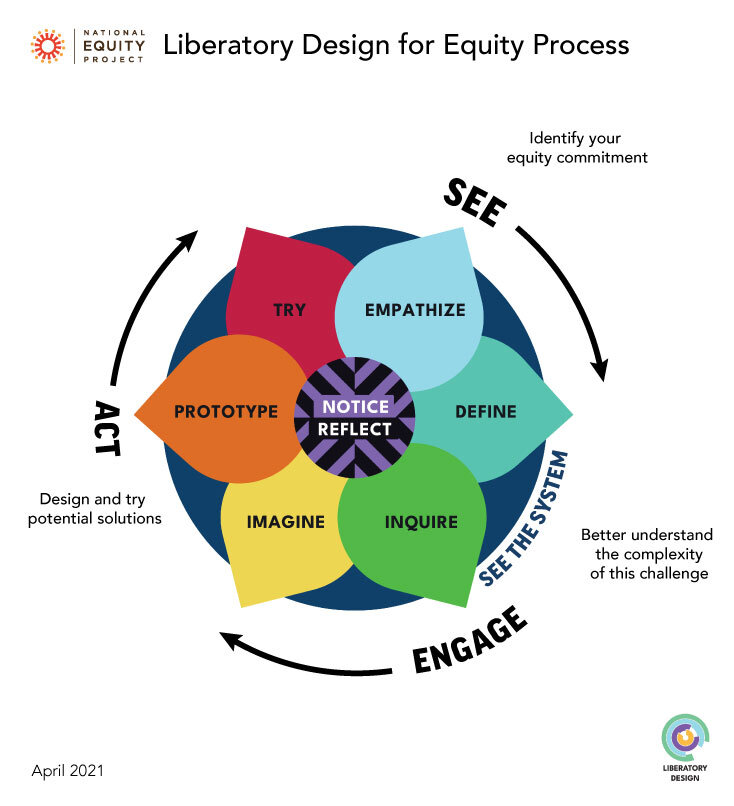

JL: For those of our readers who haven’t seen it, the Liberatory Design model is presented as a deck of cards that consist of mindsets (beliefs, values, and stances) and modes (practices). Some examples of the mindsets are (1) work to transform power, (2) practice self-awareness, and (3) recognize oppression; some examples of the modes are (1) see the system, (2) empathize, and (3) inquire. Can you describe the role the modes and the minsets play in the process? And examples of how people have worked with the deck?

TM : It may be helpful to think of the modes and mindsets as two halves of a whole or more like a yin and yang, if you will. A simple way that I think about them is that the mindsets are ways of being, and the modes are ways of doing for equity leaders, and they’re kind of inseparable.

There’s no set way to work with the design deck. It is a kind of process container, rather than a “strategy.” The deck is a resource that can be drawn upon to support equity work on a daily, ongoing basis. Oftentimes the mindsets are a more accessible starting place for folks, especially people who don’t have any knowledge of human centered-design or design thinking. They’re not a substitute for more foundational equity learning, but they name oppression and open up more liberatory ways of working with each other.

Let’s take one of the mindsets, “transforming power.” There are predictable types of power dynamics because of people’s roles and identities who are in a space together. But what happens when we shift the ways that that power tends to play out, and people who have had less power feel they have more? Specifically the power to be who they are and the power to bring their ideas forward and feel heard and the power to be in relationship with folks differently. Then, folks who traditionally sit in seats of power with more decision-making authority begin to see what it is like if they let go of some of that power. It can be liberating for them in a different way.

Let’s take one of the mindsets, “transforming power.” There are predictable types of power dynamics because of people’s roles and identities who are in a space together. But what happens when we shift the ways that that power tends to play out, and people who have had less power feel they have more? Specifically the power to be who they are and the power to bring their ideas forward and feel heard and the power to be in relationship with folks differently. Then, folks who traditionally sit in seats of power with more decision-making authority begin to see what it is like if they let go of some of that power. It can be liberating for them in a different way.

I was talking with a leader in Washington State who is a woman of color in the early learning and early childhood space. She uses the mindsets as personal resources for herself as she navigates the often oppressive spaces that she’s working within. She shared how they support her in maintaining a sense of agency, and remind her how she wants to be when she goes into meetings and certain spaces. The mindsets help her set her intentions and decide how she wants to show up. She uses them as little nudges and invitations and reminders in the way that she works with folks.

As for the modes, they’re organized like a flower. The modes of “notice” and “reflect” sit at the center of the petals. These two modes help us stay grounded in self-awareness (like a mirror) and situational awareness (like a window). We keep coming back to Notice and Reflect in a process, and connecting to the mindsets. And then determining which other modes, or petals, we need to engage in next, like further listening (empathy) or learning (inquire) or prototyping.

JL: Are there a couple pieces of advice that you would give organizations embarking on their efforts to create more equitable teams, organizations, and systems?

TM: First, I think it’s really important to create conditions that allow people to build their own relationship with this approach so that they feel that it doesn’t just exist as part of some external authority. Then they can ask themselves: How do the cards speak to you? How do they connect with things that you already do or ways that you already think? Where do they feel like they stretch you? What do they make you feel? What ideas do they give you? That way you can really promote a sense of kind of ownership. People tend to have mental models of processes that have components and sequences, and must be practiced with fidelity — these models generally don’t feel liberatory and work against feeling this kind of ownership.

And because equity work is complex and risky, another piece of advice is to create safer ways to fail when experimenting with Liberatory Design. I would suggest practicing first in a low-stakes context, e.g. with a few trusted colleagues in your own organization, so you can learn and build confidence and creativity to keep going further in more complex situations.

One example of less safe failure in a higher stakes, more complex context would be the process of co-designing strategies for greater equity with young people in an educational setting. It takes more than just inviting students to the table – the adults need to pay attention to how adultism manifests and how students experience even well-intended adults tokenizing or marginalizing the young people in the room, rather than working in ways that would bring forward their perspectives and potential power. The Liberatory Design mindsets and modes can support complex work like this. We’ve developed a set of resources that support co-design partnership work with youth and adults.

JL: What advice do you have specifically for people who are not formal organizational leaders that want to introduce Liberatory Design principles in their workplace?

TM : It is important to recognize that everybody has a sphere of influence, regardless of where they are in an organization. We’ve seen Liberatory Design take root in very different starting conditions.

In some instances, it starts with leadership. The strength of that approach is that from the get-go, there is an intention that this will become an organizational way of thinking and working.

We’ve also seen instances where it has been introduced from the bottom or middle up, where folks get onto it and realize it’s really helpful in their particular realms of the organization and then they go to their leadership to ask them to help create conditions for further practice of Liberatory Design.

There are a few things that you can try within your sphere of influence if you are not a part of organizational leadership. For instance, you can share the Liberatory Design mindsets with team members and what you’ve learned about using them, how they have helped you, and how they may view them. You can also start to guide your group in a way that is informed by the modes, e.g. “What if we did some listening with the people we’re designing for to inform our work?” or “What if we share a rough prototype to get feedback before we implement?” or “What if we paused to set some intentions about how we want to be working together before we jump into our agenda?” In that way, you can become increasingly explicit or transparent about some things you’re trying.

People generally experience so many constraints that shape their work, and so there’s something empowering about getting their hands on an approach that allows them to imagine different ways of working with each other and with those they serve. And then they can start to experiment with being in different relationships with the people that they serve, even if they’re just starting with listening more intentionally. My advice is to just get started — and try things, learn, and move forward!

Interested in learning more about how Liberatory Design has been applied within an organization? Check out our prior blog Liberatory Design Part 1: An Equity Learning Journey for examples. Also be sure to watch this space for resources on ethical storytelling in the coming months.

For our fourth installment of our Elevate Q&A series examining issues pertinent to the philanthropic sector and nonprofits, I am chronicling my own journey to learn how to nurture a more equitable organizational culture through the use of a process called human-centered design. In Part 2 of this blog, I sit down with Tom Malarkey of the National Equity Project (NEP) to learn more about how the NEP was inspired by human-centered design thinking to develop Liberatory Design, its model for interrupting inequity.

A Human-Centered Design Approach to Equity Work

During the past year, and building on my earlier Q&A with April Walker of Philanthropy for the People, I’ve been interested in what it takes for an organization to transform its culture into a more equitable one. To that end, I read Minal Bopaiah’s excellent book on how organizations can use human-centered design to achieve a more fair and just workplace. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the  term human-centered design (I certainly wasn’t!), it is a creative problem-solving technique that was first employed in the engineering field by the Stanford University design program. It prioritizes people and considers the complex systems within which they operate. It is now widely utilized across disciplines, and as I realized, can be a thoughtful, process-oriented approach to IDEA+J work.

term human-centered design (I certainly wasn’t!), it is a creative problem-solving technique that was first employed in the engineering field by the Stanford University design program. It prioritizes people and considers the complex systems within which they operate. It is now widely utilized across disciplines, and as I realized, can be a thoughtful, process-oriented approach to IDEA+J work.

I was now eager to engage, so I began looking for some interactive opportunities, such as trainings, that would enhance this learning and provide me with more tools and resources. That’s when I came across the National Equity Project and its human-centered, Liberatory Design approach to equity work.

The National Equity Project (NEP) is a nonprofit, social impact organization committed to increasing the capacity of people to achieve thriving, self-determining, educated and just communities. NEP focuses on systemic change through leadership development, by supporting leaders across systems to build culture, conditions, and competencies for excellence and equity in school districts, organizations, foundations, and communities.

What is Liberatory Design? Think Mindfulness Practice for Equity

I was excited to discover that The National Equity Project had developed a creative way of problem-solving to address equity challenges. Team members can seek to SEE and understand the territory they are navigating, to ENGAGE others to make meaning of the current situation, and then ACT to address the equity challenge and learn from that action.

The power of Liberatory Design comes from its ability to help us better understand equity challenges in highly complex interconnected systems, to see ways systems of oppression are impacting our context, to root our decision-making in our values, to combat status quo behavior with deep self-reflection, and to learn and change in a fast-moving, meaningful way. The way forward is led by noticing, experimenting, learning, reflecting, and repeating. Liberatory Design is structured to build equity leadership capacity to create real change with the communities within which you work.The process itself, as well as the outcomes, are building towards greater collective liberation. It recognizes that the required mindset is not one where work is linear or where boxes are ticked off in a sequential fashion.

The power of Liberatory Design comes from its ability to help us better understand equity challenges in highly complex interconnected systems, to see ways systems of oppression are impacting our context, to root our decision-making in our values, to combat status quo behavior with deep self-reflection, and to learn and change in a fast-moving, meaningful way. The way forward is led by noticing, experimenting, learning, reflecting, and repeating. Liberatory Design is structured to build equity leadership capacity to create real change with the communities within which you work.The process itself, as well as the outcomes, are building towards greater collective liberation. It recognizes that the required mindset is not one where work is linear or where boxes are ticked off in a sequential fashion.

With my Elevate professional development dollars, I signed up for a three-hour webinar, Introduction to Liberatory Design (note that NEP also offers a more comprehensive six-week training!), where I was able to engage in small group discussions and network with educators as well as nonprofit and foundation leaders. During the workshop, I realized how much the Design mindsets are similar to mindfulness practice– that they are a continuous process of learning and extending ourselves. It also struck me that they are really about ways to live and could be applied beyond working environments.

Liberatory Design in Action

So how has Liberatory Design been used by organizations to address their equity challenges and create new opportunities? Here are just a few examples:

The Kenneth Rainin Foundation engaged Liberatory Design to be more responsive to its community and its grantees and to improve early childhood literacy in the Bay Area city it serves.

The Kenneth Rainin Foundation engaged Liberatory Design to be more responsive to its community and its grantees and to improve early childhood literacy in the Bay Area city it serves. - A Charter School Management Organization applied Liberatory Design to transform its staff into one that was more reflective of the students and families it serves, with attention to BIPOC recruiting and retention barriers and leadership development.

- The Northwest Regional Education Service District, which serves four counties in Northwest Oregon, formed several site-based equity learning teams trained in Liberatory Design to build their internal culture around equity action, move forward on an antiracist multicultural continuum, and improve its systems to better support the community.

Interested in learning more about Liberatory Design and what it could do for your organization? Download the free English or Spanish deck of cards here. And watch this space for Part 2 of this blog, where I sit down with one of Liberatory Design’s originators, Tom Malarkey of the National Equity Project.

If you’re a grant seeker, you’ve likely encountered these scenarios.

Scenario 1: You have an existing, positive relationship with a funder. You’ve submitted a proposal for an expanded or new initiative you thought would interest them, but you received a polite decline.

Scenario 2: You identified a perfect new funding prospect. You submitted an inaugural proposal after receiving the greenlight on an LOI, but ultimately the funder did not make an award.

We’ve all been there.

No one relishes hearing the word NO in response to a funding request. While sources vary, an estimated 80% of grant proposals are declined, so any grantseeker is bound to experience their share of rejections. But when you consider – as in all things in life! – that timing is everything, a “No” doesn’t have to remain a “No” for all time. It might help to think of “No” as “Not right now.”

To that end, the team at Elevate pulled together a few of our tried-and-true tips to help you convert a funder NO into a future YES.

1. Open yourself to feedback.

There are many factors that go into funding decisions, both subjective and objective. While you believe in your mission and your organization does excellent work, don’t let that stand in the way of seeing how you can get another bite at the apple. Treat the declination as a valuable learning experience.

There are many factors that go into funding decisions, both subjective and objective. While you believe in your mission and your organization does excellent work, don’t let that stand in the way of seeing how you can get another bite at the apple. Treat the declination as a valuable learning experience.

In addition to graciously thanking the funder for their consideration, invest the time in asking what you could do differently to increase your chances of securing the grant in the next cycle.

If a funder shares any questions or concerns that arose from the proposal, use these inputs to help you shore up those elements for the next grant cycle, make your proposal more compelling, or strengthen an appeal to a different funder who may be interested in your project.

Additionally, in the case of funders that you have not been able to cultivate prior to a request, your first grant proposal might simply be your opportunity to introduce yourself. Consider that even if a proposal was declined, if it opened the door for you to develop a relationship with a new funder, it was by no means a waste of time or effort. Use any communication as an opportunity to reiterate your alignment with the funder’s interests and ask for feedback and an opportunity to apply again in the future.

2. Request a follow-up conversation.

Not all program officers have the time or capacity to hold follow-up conversations about a declined proposal, but many do! Unless they explicitly state otherwise, you should absolutely take the opportunity to request feedback from the funder about your proposal. Request a phone call or meeting, and ask them how you may position yourself to be a more competitive applicant next time around. You can also gauge their interest in other facets of your programming in case something your organization does interests them more than what you originally proposed.

Not all program officers have the time or capacity to hold follow-up conversations about a declined proposal, but many do! Unless they explicitly state otherwise, you should absolutely take the opportunity to request feedback from the funder about your proposal. Request a phone call or meeting, and ask them how you may position yourself to be a more competitive applicant next time around. You can also gauge their interest in other facets of your programming in case something your organization does interests them more than what you originally proposed.

A meeting with a foundation program officer or Board member is a chance to get some behind-the-scenes information. For example, one Elevate team’s client was ostensibly within the funder’s geographic footprint based on eligibility criteria. However, upon speaking to the program officer, our client learned that the foundation had yet to ramp up their giving in the specific neighborhood where the organization is situated, and that they plan to do so the following year. With this encouraging news, the Elevate team planned to submit another request when the foundation was more likely to award a grant to our client.

Alternatively, if it’s challenging to get a meeting on the books, you could ask the funder via phone or email whether they would encourage your organization to reapply during the next grant cycle. Their response may end up yielding some useful insight about your likelihood of securing funding in the future.

3. Seek opportunities to expand your funder network.

For the most part, foundations operate within a landscape of like-minded organizations, just as nonprofits do. Many funders maintain networks of other philanthropic organizations that share aspects of their giving priorities, and they may even participate in an affinity group of foundations with shared interests. For this reason, after a foundation declines your proposal, it can be valuable to appeal to the funder’s expertise when it comes to other organizations that share their funding priorities. Ask them about other organizations or foundations that they think may be interested in your work, and don’t be afraid to request an introduction to a good point of contact.

For the most part, foundations operate within a landscape of like-minded organizations, just as nonprofits do. Many funders maintain networks of other philanthropic organizations that share aspects of their giving priorities, and they may even participate in an affinity group of foundations with shared interests. For this reason, after a foundation declines your proposal, it can be valuable to appeal to the funder’s expertise when it comes to other organizations that share their funding priorities. Ask them about other organizations or foundations that they think may be interested in your work, and don’t be afraid to request an introduction to a good point of contact.

4. Offer to keep the funder in the loop about your organization.

Fundraising is a long game, so it’s important to be persistent when building a relationship with a grantmaker. As part of your stewardship efforts, you might offer to send periodic updates about your organization’s work or seek to connect with a potential funder through a site visit or a networking event. As a result, they may better understand your work – and your alignment with their interests – the next time you request funding.

5. Refine your prospecting strategy.

Sometimes, a “No” truly is a “No.” If a program officer makes this explicit, it is not going to do you any good to persist—and may harm your organization’s reputation if you do!

Sometimes, a “No” truly is a “No.” If a program officer makes this explicit, it is not going to do you any good to persist—and may harm your organization’s reputation if you do!

However, this does not mean there isn’t something to learn from the scenario. Reflect on where you misunderstood your organization’s alignment with the funder’s interest, and use this to refine your prospecting strategy so that you can focus on grant opportunities that you are more likely to win.

Consider this example: A nonprofit organization focused on providing services to people who are unhoused submits a grant request to a funder with a broad priority of “housing security”. The request is declined, and after following up to ask for feedback from the program officer, the organization learns that this grantmaker invests in advocacy and systems change organizations rather than those providing direct services. With this information, the nonprofit refines its prospecting strategy to ensure that in the future it pursues grant opportunities with a clear interest in funding direct services.

The bottom line: In order to build a grant program, you are going to hear “No.” But do not despair! Your next steps will make all the difference when it comes to building relationships and refining your grantseeking strategy. And, sometimes you can make bad news work for you!

For more on how to make the most out of a declination, check out this article on Candid. Relatedly, see our blogs on “5 Reasons to Cultivate Relationships with Funders” and “5 Ways to be Pleasantly Persistent with Funder Cultivation.”

Welcome back for a third installment on our Elevate Q&A series, where we “pass the mic” to a member of our extended philanthropic family to examine issues pertinent to the sector and nonprofits! (If you missed our previous conversations, please check out our Q&As with Wade Munday, Bridgestone America’s Director of Corporate Philanthropy; and April Walker, founder of Philanthropy for the People, where we explored some of the challenges and opportunities nonprofits and philanthropists face in pursuing a more equitable approach to their work.)

This time, I spoke with Brian Rosenbaum, the Development Officer for A Place Called Home (APCH), where he holds a portfolio of 150 major and mid-level donors and oversees the organization’s monthly giving program..

For 30 years, A Place Called Home (APCH) has provided South Central Los Angeles youth with a safe, nurturing environment and proven programs in the arts, education, and wellness to help them improve their economic conditions and develop healthy, fulfilling, and purposeful lives. APCH has directly served more than 20,000 youth members through its core school day, after school and summer programming, and over 150,000 local residents through family and supportive services including food, clothing, and holiday toy distributions, counseling, voter education, and community organizing.

Brian is a Southern California native with 18 years of U.S. and international nonprofit experience. He earned his BA in Psychology and Spanish from UCLA and his Masters in Social Work from Columbia University, specializing in program development and community organizing.

My conversation with Brian covered how he leverages his social work training in his current fundraising work, what he sees as the key to successful partnerships with donors, and how he has implemented DEI principles throughout his career.

What It Takes to Successfully Engage Donors

Johnisha Levi: How do you draw upon your background in social work in your current fundraising role?

Brian Rosenbaum: The core values of social work include meeting people where they are, leveraging a strengths-based approach, and capacity building. Each of these is applicable to nonprofit fundraising and communications.

As a nonprofit leader, I also consider ways in which we can hold space for each other to feel seen, to bring our full selves to our work, and to make our best contributions in this world. It’s about discovering ways to pour inspiration into people.

JL: I imagine these values help you to build strong and trusting relationships among colleagues. How would you describe your approach to building relationships with major donors and other partners?

BR: Something that I like to talk about is how “relationship” is sort of a neutral word. You can have a good relationship. You can have a bad relationship. You can have a distant relationship or a close one. On the other hand, a partnership has only one connotation. If you are partners, you are paired.

In a true partnership, everyone gets their needs met, everyone feels heard and seen. And then you grow together and evolve. That’s how I see my role within my staff, with other departments, and with donors; we are partners, and more specifically, we are partners in impact.

When I was at United Way of Greater LA, one of the ways that we described the role of a fundraiser was as a “philanthropic concierge”. It’s all about understanding the impact that a donor wants to make, their priorities, their capacity, their affinity, and their connection to the cause, and then using this information to compose a menu that is in alignment with their passion and interest with our very real funding needs. In implementing this approach, we created meaningful partnerships with donors that led to real impact for our community.

JL: Can you give me an example of your work with a prospective donor that exemplifies this idea of partnering in impact?

BR: I will share an example of resuscitating a relationship that lapsed prior to my arrival at the Los Angeles Ronald McDonald House. I told my boss, “Challenge accepted.”

BR: I will share an example of resuscitating a relationship that lapsed prior to my arrival at the Los Angeles Ronald McDonald House. I told my boss, “Challenge accepted.”

First, I did a little bit of email outreach to the lapsed donor, and when I didn’t get anything back, I got her on the horn. She was at the grocery store and said she would call back, but she didn’t.

I was tenacious. I got her on the phone again. She shared that she was really disappointed in the lack of appreciation and stewardship. And you know what? Sometimes you just gotta listen. And as a social worker, I embrace any chance I get to listen to people, to really understand what’s going on for them. I told her that I was mortified and angry to hear that she didn’t get the recognition that she deserved. And that she deserved to know the impact of her gift.

I explained how I would do better. I made a list of promises to her, and I delivered on them. Then I brought her in for a tour to see the impact of her gift. At the end of the tour we were sitting down in the dining room having some coffee when she asked about our current needs. I shared a few of our funding priorities, and she said, “Good. Send us a list. You know the things we care about. We’ll see what we can do.”

She and her husband care about safety and security, and comfort and care. So we created a menu with various projects and different price points that were aligned with these interests.

I talked with her several months later. It took some time. But at that point, we settled on a project that satisfied both of our needs – at their previous giving level – and we transformed the broken relationship into a partnership.

Most Important Piece of Advice for a New Fundraiser

JL: You’re clearly a seasoned cultivator and partnership-builder. What advice would you give to a new fundraiser about how to approach donor cultivation?

BR: I would say, lean into curiosity, be a sponge. Whether you are stewarding or cultivating donors, know those lists of questions to ask donors from a place of authenticity.

BR: I would say, lean into curiosity, be a sponge. Whether you are stewarding or cultivating donors, know those lists of questions to ask donors from a place of authenticity.

One of my favorite questions to ask that people don’t expect is, “How did you become generous?”

It is also crucial to have genuine curiosity about how a donor would like to be engaged. For example, asking, “Can we schedule some time in two weeks to reconnect to see what you thought about this idea?” Or offering, “Can I send you a quarterly update, because you’re part of our impact?” People rarely say no to this last one.

Tenacity is also important: keep trying. We have to respect donors’ wishes but sometimes it is just a ‘no’ for right now.

The Importance of Applying a DEI Lens

JL: Nonprofits and philanthropists are increasingly focused on ensuring that diversity, equity, and inclusion is the lens through which they implement social change. Can you share a little about your own journey with DEI over the course of your career? What are some of the key lessons you’ve learned?

BR: Graduate school really helped me recognize the power and privilege that I bring into rooms and the fact that every white person is on their own journey of unlearning their racism. Biases are in the air that we breathe. You’ve got some sexism in you. You’ve got some heterosexism in you. You’ve got some ableism in you. You’ve got some nativism in you.

It’s like the moving walkway at the airport; you’re just going to be carried to the end unless you start walking the other way. But it takes a lot of self-work.

I committed myself to doing that work when I came back to LA after grad school, starting with getting involved in AWARE-LA (Alliance of White Anti-Racists Everywhere-Los Angeles). They hold both white-only spaces and multi-racial coalition building spaces with the aim of holding each other accountable and in recognition of the fact that people of color should not have to teach white folks about our own racism.

Subsequent to that, and surrounding the events of 2020 following George Floyd’s murder, I was part of an organization that really took advantage of the opportunity to unpack its past. It opened up a giant, very important conversation about some historical trauma that had happened in the organization and that was still affecting staff.

Out of this process came a renewed sense of responsibility, accountability, and personal growth; you don’t get that opportunity very often.

JL: How do you bring these values that have shaped your own thinking about DEI into your partnership building and donor engagement work?

BR: I am passionate about ethical storytelling. This means presenting our clients as the heroes of their own story, not people who are broken and need to be fixed. We might be experts on suicide prevention, or food insecurity, or homelessness, but the client is the teacher: they are the experts on their experiences, and should be positioned as such. Sometimes I explain this as seeing the two sides of the coin when it comes to a person. Everyone has both strengths and struggles.

BR: I am passionate about ethical storytelling. This means presenting our clients as the heroes of their own story, not people who are broken and need to be fixed. We might be experts on suicide prevention, or food insecurity, or homelessness, but the client is the teacher: they are the experts on their experiences, and should be positioned as such. Sometimes I explain this as seeing the two sides of the coin when it comes to a person. Everyone has both strengths and struggles.

Ethical storytelling is about finding the balance – truthfully representing stories and situations so that we are educating our audiences about the issues that people are facing, while also including the nuances, the complexities, all of the realities of the situation.

Every time we don’t use an ethical storytelling lens, we do damage by reinforcing negative stereotypes. Imagine the negative impact on a client who actually reads that story in the newsletter or in the annual report or on social media!

With that client in mind, I aim to apply a frame of ethical storytelling in my work as a fundraiser.

JL: That is sage advice! What are a few best practices when it comes to ethical storytelling that you employ?

BR: I have the site www.ethicalstorytelling.com bookmarked and use it all the time. For instance, there is a great media consent form that we utilize. It offers individuals the power to consent to share their story or their likeness in a way that is comfortable for them.

It is also important to make determinations about how to use client images and video in a way that is complementary and uplifting, as well as to include clients in the editing process, and to allow them to approve content.

Interested in learning more about ethical storytelling principles? Sign up for our August 2024 webinar, Introducing and Empowerment Framework for Grant Writing, and look for more resources coming your way on this blog!

In spring 2023, MacKenzie Scott’s Yield Giving launched an open call for community-led, community-focused organizations. It received over 6,000 applicants, including 31 Elevate clients who participated. At long last, in March 2024, 361 awards were announced. The process was rigorous, and each organization that participated deserves major kudos!

Elevate is thrilled to share that six of our nonprofit partners were selected as awardees in Yield Giving’s 2023 Open Call. All together, these organizations secured $11 million in funding from Yield Giving for their crucial work in housing, substance use treatment and prevention, education, advocacy, and more. Five of Elevate’s clients were among the top tier of applicants and received $2 million each, and one organization was selected for the next tier and received a $1 million award.

Ultimately 1 out of 5 Elevate clients who applied won (compared to 1 out of 17 for the overall pool.)

Of course, Yield Giving was just one of many competitive opportunities Elevate teams and clients pursued (and secured!) in the past year. We are proud of all of the wins – large and small – that each of our clients secure to advance their important work.

For more on how we measure success at Elevate, check out our 2023 By the Numbers and 2023 Meaningful Wins blog posts! We look forward to continuing to partner with and support ALL of our nonprofit clients in 2024 and beyond!

As we reported in our most recent blog, Elevate closed out 2023 by helping our clients win in excess of $100 million in grant funding! (Balloons effect) Because we meticulously collect data on our work with clients, we know that the average and median grants were $131,000 and $30,000, respectively. However, the size of a grant only tells part of the story. A grant of ANY size can have a significant impact on an organization. A grant may be particularly significant because it is the result of a new funder relationship or an award from a current funder for a new priority. An award may be significant because it supports expansion of current work or new initiatives, or builds capacity to help an organization grow and develop as it moves into a new phase of its life cycle.

Accordingly, we are excited to spotlight just a few of last year’s meaningful wins that helped our partner organizations achieve their fundraising objectives.

Jewish Family Service of the Desert Awarded $200,000 from the Houston Family Foundation

Founded on the Jewish principle of healing the world, Jewish Family Service of the Desert has addressed the social services needs of the Jewish and general community throughout California’s greater Coachella Valley for over 40 years. JFS of the Desert serves thousands of people a year with mental health, school counseling, emergency assistance, and special programming. The organization started working with Elevate in 2023 as one of its Comprehensive Grant Writing Services (Comprehensive Grant Writing Services) clients.

Founded on the Jewish principle of healing the world, Jewish Family Service of the Desert has addressed the social services needs of the Jewish and general community throughout California’s greater Coachella Valley for over 40 years. JFS of the Desert serves thousands of people a year with mental health, school counseling, emergency assistance, and special programming. The organization started working with Elevate in 2023 as one of its Comprehensive Grant Writing Services (Comprehensive Grant Writing Services) clients.

2023 Meaningful Win: Last year, The Houston Family Foundation awarded JFS of the Desert a total of $200,000, with $150,000 allocated to its Case Management Program, providing individuals who are low-income with no-cost assistance in accessing available benefits; and $50,000 to increase current and future access to mental health services in the Coachella Valley.

IN Series Awarded $15,000 from Humanities DC

IN Series is the standard-bearer for innovative opera theater in Washington, DC. Working with local artists and diverse communities worldwide to create novel works grounded in opera and song, IN Series challenges and reimagines these forms, folding in an expanding range of aesthetic and cultural traditions. The organization has been working with Elevate through Comprehensive Grant Writing Services for five years.

IN Series is the standard-bearer for innovative opera theater in Washington, DC. Working with local artists and diverse communities worldwide to create novel works grounded in opera and song, IN Series challenges and reimagines these forms, folding in an expanding range of aesthetic and cultural traditions. The organization has been working with Elevate through Comprehensive Grant Writing Services for five years.

2023 Meaningful Win: IN Series was awarded a $15,000 grant from Humanities DC to support its Shakespeare Everywhere Festival Scholar in Residence Lecture Series. The lecture series featured Shakespeare scholar, Professor Marjorie Garber, as she discussed The Promised End, an operatic reimagining of Shakespeare’s King Lear featuring the music of composer Guiseppe Verdi. The production and lecture series were produced as part of the Shakespeare Everywhere Festival, with the following partnering institutions: IN Series, Folger Theater, Studio Theatre, Shakespeare Theater Company, Washington Ballet, and the Washington National Opera. You can read more about the Shakespeare Everywhere festival here.

Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition Awarded $50,000 from the Tides Foundation

Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition (MEJC) works to achieve a clean, healthy, and safe environment for Michigan residents. The organization takes a multi-faceted approach to systems change by aligning on intersectional goals with statewide power-building organizations and small grassroots groups for policy change and disruption. MEJC became an Elevate Comprehensive Grant Writing Services client in 2022.

2023 Meaningful Win: The Healthy Democracy Fund, a fund of Tides Foundation—a grantmaking initiative that is committed to building a more inclusive democracy by shifting power to leaders and communities who have been historically excluded from participating in our nation’s future—awarded MEJC $50,000 to support its general operating costs for planned civic engagement work. This win is particularly meaningful as it represents a shared goal between MEJC and its funding partners around shifting power to—and building power within—impacted communities to change the status quo.

Jewish Family Service of Seattle Awarded $40,000 from the Boeing Employees Community Fund

Inspired by Jewish values, JFS of Seattle helps individuals and families in Puget Sound, Washington achieve well-being, health and stability through a range of supports that include financial assistance, outreach and education, and services for refugees and immigrants, older adults, and people with disabilities. JFS of Seattle is one of Elevate’s oldest Comprehensive Grant Writing Services clients: our partnership is 8 years strong (and counting!)

Inspired by Jewish values, JFS of Seattle helps individuals and families in Puget Sound, Washington achieve well-being, health and stability through a range of supports that include financial assistance, outreach and education, and services for refugees and immigrants, older adults, and people with disabilities. JFS of Seattle is one of Elevate’s oldest Comprehensive Grant Writing Services clients: our partnership is 8 years strong (and counting!)

2023 Meaningful win: One of JFS Seattle’s priorities is supporting and welcoming immigrant and refugee communities to the Puget Sound region. A $40,000 award from the Boeing Employees Community Fund in September 2023 allowed JFS of Seattle to purchase a minivan for the purposes of transporting folks who are resettling in the area. For example, the van will be used to pick up newly arrived refugees from the airport, accompany clients to registration appointments for benefits or to medical appointments, transport clients to appointments for enrolling their children in school or in English language classes, and transport clients to job interviews.

GALA Hispanic Theatre Awarded nearly $80,000 from Learn24 Out of School Time

GALA (Grupo de Artistas LatinoAmericanos) Hispanic Theatre is a National Center for Latino Performing Arts in Washington, DC. Since 1976, GALA has been promoting and sharing the Latino arts and cultures with a diverse audience, creating work that speaks to communities today, and preserving the rich Hispanic heritage for generations that follow. By developing and producing works that explore the breadth of Latino performing arts, GALA provides opportunities for the Latino artist, educates youth, and engages the entire community in an exchange of ideas and perspectives. GALA is a Comprehensive Grant Writing Services client that has partnered with Elevate for eight years.

GALA (Grupo de Artistas LatinoAmericanos) Hispanic Theatre is a National Center for Latino Performing Arts in Washington, DC. Since 1976, GALA has been promoting and sharing the Latino arts and cultures with a diverse audience, creating work that speaks to communities today, and preserving the rich Hispanic heritage for generations that follow. By developing and producing works that explore the breadth of Latino performing arts, GALA provides opportunities for the Latino artist, educates youth, and engages the entire community in an exchange of ideas and perspectives. GALA is a Comprehensive Grant Writing Services client that has partnered with Elevate for eight years.

2023 Meaningful Win: GALA received $79,984.00 in grant funding from Learn24 Out of School Time in support of Paso Nuevo, the organization’s free, year-round bilingual, inclusive theatre education program offered to high school students between the ages of 14 and 19. In addition to providing acting training, playwriting, and mentorship, students can earn community service hours, receive performance stipends, go on field trips, and train for future employment and leadership opportunities.

We are so pleased to share with you this small sample of the hundreds of meaningful wins our clients secured with the support of their Elevate teams in 2023! If you work with a nonprofit and are interested in learning about how Elevate can help you meet your fundraising goals, learn more about our services here and please get in touch!

For those of you who are regular readers of Elevate’s blog, you know what time it is. (And for those who are new readers, you are about to get a snapshot of what we are all about.). ‘Tis the season to celebrate the past year’s accomplishments while also reviewing the data related to our work and examining underlying trends. Because we at Elevate always look for the stories that data tells us. So without further ado, I introduce to you . . . 2023 Elevate by the Numbers.

Elevate’s Win Rate is Over 50% and Our Median Grant Is Up!

At the risk of sounding boastful, we are thrilled to share that in 2023, we secured over $100 million in grant funding for our clients. We’ve now hit this milestone for the third year in a row! While this NINE FIGURE total is certainly impressive, more importantly, we recognize that it represents the sum of both the larger and smaller awards that are equally vital in meeting our clients’ revenue goals. The average grant we won with our clients last year was over $131,000, and our median grant award was $30,000 (up from $25,000 in 2022). We also won the majority (56%) of all grants that we submitted and that were closed for the year. This is considerably higher than estimated national win rates (an estimated 18% of all grants submitted nationally are awarded).

At the risk of sounding boastful, we are thrilled to share that in 2023, we secured over $100 million in grant funding for our clients. We’ve now hit this milestone for the third year in a row! While this NINE FIGURE total is certainly impressive, more importantly, we recognize that it represents the sum of both the larger and smaller awards that are equally vital in meeting our clients’ revenue goals. The average grant we won with our clients last year was over $131,000, and our median grant award was $30,000 (up from $25,000 in 2022). We also won the majority (56%) of all grants that we submitted and that were closed for the year. This is considerably higher than estimated national win rates (an estimated 18% of all grants submitted nationally are awarded).

Elevate Clients are Making a Difference in 47 Cities

Last year, we worked in partnership with 168 nonprofit organizations, hailing from 15 states and 47 cities across the nation, with Washington DC, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia-based organizations leading the pack with the largest shares of our client portfolio. The nonprofits that collaborate with Elevate work in a variety of sectors: Health, Human Services, & Housing; Education & Training; and Advocacy, Policy, & Organizing represent the three largest categories of Elevate clients. Our clients’ budgets range from from $400,000 to over $1 billion, with a median annual budget of $2.5 million.

Last year, we worked in partnership with 168 nonprofit organizations, hailing from 15 states and 47 cities across the nation, with Washington DC, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia-based organizations leading the pack with the largest shares of our client portfolio. The nonprofits that collaborate with Elevate work in a variety of sectors: Health, Human Services, & Housing; Education & Training; and Advocacy, Policy, & Organizing represent the three largest categories of Elevate clients. Our clients’ budgets range from from $400,000 to over $1 billion, with a median annual budget of $2.5 million.

Because we understand that organizations have different needs based on the stage of their grants program, their capacity, and their strategic fundraising goals, Elevate does not work in a one-size fits all manner. While the majority (96) of our clients opt for our signature Comprehensive Grant Writing Service or our Ongoing Writing Retainer, we also provide start-up support through Grants Accelerator Projects and project-based writing capacity through our Writing Capacity Projects. In 2023, 16 organizations partnered with Elevate on GAPs and 25 engaged us for WCPs.

Elevate Teams Drafted & Submitted Nearly 3,000 Deliverables for Clients

You may be asking what it takes to win $100 million in grant funding. It obviously takes a lot of hard work by our talented Elevate staff (check out our swell team); more concretely, we submitted a total of 2,912 grant proposals, concept notes, reports, and letters of inquiry last year. To get the job done, we racked up in excess of 2 million zoom meeting minutes by attending over 15,000 virtual meetings in 2023. As a fully remote workforce, our 86-member staff reside in 26 states. And last year, Elevate invested $41,000 in staff professional development to support our team in developing their knowledge of IDEA+J, nonprofit financials, fundraising trends, and other topics that are relevant to our clients’ success.

You may be asking what it takes to win $100 million in grant funding. It obviously takes a lot of hard work by our talented Elevate staff (check out our swell team); more concretely, we submitted a total of 2,912 grant proposals, concept notes, reports, and letters of inquiry last year. To get the job done, we racked up in excess of 2 million zoom meeting minutes by attending over 15,000 virtual meetings in 2023. As a fully remote workforce, our 86-member staff reside in 26 states. And last year, Elevate invested $41,000 in staff professional development to support our team in developing their knowledge of IDEA+J, nonprofit financials, fundraising trends, and other topics that are relevant to our clients’ success.

Elevate Can Also Get Down

Lest you think that all of this business leaves no time for pleasure, you’d be wrong. Elevate knows how to party. Last year, we celebrated our 10th anniversary in style at the LINE hotel in Washington, DC, closing the night out with 100 sweet cupcakes. We also jammed to 1,012 songs as part of the wildly competitive Elevate Music League. When we weren’t eating, dancing, and partying, we managed to welcome four precious new Elevate tykes – congrats to the new parents!

Lest you think that all of this business leaves no time for pleasure, you’d be wrong. Elevate knows how to party. Last year, we celebrated our 10th anniversary in style at the LINE hotel in Washington, DC, closing the night out with 100 sweet cupcakes. We also jammed to 1,012 songs as part of the wildly competitive Elevate Music League. When we weren’t eating, dancing, and partying, we managed to welcome four precious new Elevate tykes – congrats to the new parents!

Interested in being a part of this winning team or perhaps learning more about our different client services to see how we might support your organization? You can find more information about our services here, or click here to learn more about open positions at Elevate.

These are some common responses from Executive Directors when asked to cultivate a new foundation partner as part of their organization’s larger grant strategy.

Cultivation is often deprioritized in order to “get proposals out the door,” but organizations that ignore the opportunity to build relationships with funding partners before making an ask are doing themselves a huge disservice. If you are looking for some talking points to convince an Executive Director to take action – or perhaps you need some motivation yourself – check out these five tips.

1. Building name recognition with the funder will help you stand out

When was the last time that you picked up a phone call from “Unknown Caller”? I’m not sure either. When you submit an application to a funder with whom you have never previously spoken, you are essentially that unknown caller in a giant virtual pile of grant applications.

When was the last time that you picked up a phone call from “Unknown Caller”? I’m not sure either. When you submit an application to a funder with whom you have never previously spoken, you are essentially that unknown caller in a giant virtual pile of grant applications.

Need proof? Elevate clients have received responses to cold submissions like this one from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation:

“We received 342 proposals and can support only 3-4 projects…”

And this one from the Aetna Foundation:

“ We received close to 1,800 applications from locations across the contiguous United States…”

Instead of resigning yourself to being one of hundreds of virtually anonymous applicants in a stack, cultivation activities give you an opportunity to develop name recognition and – maybe – build excitement with the Program Officer about your work.

Bottom line: Cultivation gives you an advantage over the unknown organizations in the pile, and it increases the likelihood that your proposal will receive serious consideration.

2. Getting clarification early could avoid a huge waste of staff time later

Philanthropy is not immune to a culture of buzzwords – innovation, strategy, moving the needle, etc. Your definition of “innovative” or “strategy” could differ greatly from the funder’s. Speaking with a Program Officer before you spend a great deal of time and effort on a complex proposal could save you the trouble of learning later that your program is not quite innovative enough.

Alternatively, it may present you with the opportunity to convince the Program Officer otherwise. You can prevent your proposal from being tossed aside during a high level review if you have clarified definitions and expectations in advance.

Bottom line: Cultivation could save the organization time and money.

3. Insider information is not shared with the outsiders

Yes, the funder’s website or RFP will outline the official funding priorities, application guidelines, and deadlines. Do you know what it won’t share? You won’t read about the not-yet-official funding priorities that may be incredibly well-aligned with your program and that may even offer a much larger funding amount. The website also won’t recommend that you apply in this current grant cycle because the next one is much more competitive for a smaller pot of money.

Yes, the funder’s website or RFP will outline the official funding priorities, application guidelines, and deadlines. Do you know what it won’t share? You won’t read about the not-yet-official funding priorities that may be incredibly well-aligned with your program and that may even offer a much larger funding amount. The website also won’t recommend that you apply in this current grant cycle because the next one is much more competitive for a smaller pot of money.

A conversation with a human – via email, phone, or Zoom – is much more likely to give you information that has not yet been made public (or may never be) .

Bottom line: Cultivation gives you access to information that others do not have.

4. Even if a funder isn’t interested, they may know someone who is

Funders network too. Program Officers are aware of who else is granting money to organizations in their issue area and geographical community. Groups such as the Philanthropy Network Greater Philadelphia, Philanthropy DMV, and other regional funder networks and issue-based affinity groups regularly bring together foundations with similar goals.

When you speak with a Program Officer on the phone, it is absolutely possible that they make recommendations for where else you might pursue funding. And you don’t have to wait for them to offer – why not ask, “Do you know of any other foundations who may be interested in supporting this project?” Heck, they may even be willing to make an introduction for you!

Bottom line: Cultivation multiplies new relationships (and new funding opportunities).

5. Even rigorous review processes have some measure of subjectivity

At least as far as we are aware, foundations do not feed their grant proposals into an AI system to review and make funding decisions. Review Committees are made up of humans, and these humans decide which applicants will receive their much coveted dollars.

At least as far as we are aware, foundations do not feed their grant proposals into an AI system to review and make funding decisions. Review Committees are made up of humans, and these humans decide which applicants will receive their much coveted dollars.

Cultivation connects your organization’s people to the Foundation’s people in a way that can not be achieved through words on a screen.

Bottom line: Cultivation is the not-so-secret way to humanize your work for the humans making decisions.

Ready to get started? Check out this blog post with tips on how to keep in touch and build meaningful relationships with your funding partners.

We are back with the second in a series of blogs where we “pass the mic” to another member of the multifaceted philanthropic community to gain their personal perspective on issues relevant to the sector and nonprofits. (If you missed our first Q&A, be sure to check out our earlier discussion with Philanthropy for the People’s April Walker.)

This time, I sat down with a fellow Nashvillean, Wade Munday. In January 2023, Wade assumed the role of Bridgestone Americas’ first Director of Corporate Philanthropy and Social Impact, where he is responsible for advancing and directing the strategy and execution of the company’s philanthropic and social programs. He manages the operations of Bridgestone Americas Trust Fund, corporate philanthropy, and workplace giving.

Wade has 15 years of experience working with nonprofits, corporate trusts and government-affiliated organizations. His career in the nonprofit sector began at Children’s Hospital Boston. He was the founding executive director of two smaller nonprofits and the Co-Director of the Addis Clinic, a nonprofit focused on extending access to healthcare in communities throughout Africa. Wade is a graduate of Vanderbilt Divinity School, where he studied under such luminaries as civil rights icon Reverend James Lawson. He credits his time at Vanderbilt with helping to shape his strong social justice orientation.

My conversation below with Wade includes an exploration of his current corporate philanthropy role, guidance for nonprofits seeking institutional funding, and how he has centered Diversity Equity & Inclusion principles in his own work.

Leveraging Bridgestone’s Expertise in Creating Social Impact

Johnisha Levi: Can you share with us a bit about the lead up to creating this new Corporate Philanthropy and Social Impact role at Bridgestone? Before you came, what was the structure for making decisions and awarding support?

Wade Munday: In the 1980s, Bridgestone, the largest rubber manufacturer in the world, acquired Firestone, along with all of the companies associated with it. And within those companies was a trust fund that was seeded initially with a $1.5 million endowment. The trust fund was originally established to benefit the Akron, Ohio community. With Bridgestone, this was extended to supporting communities around the country. With this change, the decision-making became very diffuse and guided by team members’ and executives’ interests.

Wade Munday: In the 1980s, Bridgestone, the largest rubber manufacturer in the world, acquired Firestone, along with all of the companies associated with it. And within those companies was a trust fund that was seeded initially with a $1.5 million endowment. The trust fund was originally established to benefit the Akron, Ohio community. With Bridgestone, this was extended to supporting communities around the country. With this change, the decision-making became very diffuse and guided by team members’ and executives’ interests.

We were and still remain the largest contributor to the United Way of Greater Nashville. That relationship goes back 30 years, because our CEO at the time was very invested in social services and strengthening the social safety net of Nashville. We have also prioritized investing in athletes with different abilities through Adaptive Sports Ohio because it aligns with our sports partnerships (Bridgetone sponsors both the Olympics and the Paralympics). We have given money to many other nonprofit organizations, but it is fair to say our reach was broad, not deep.

JL: What are your current priorities in your new role?

WM: Going forward, Bridgestone is looking to co-create impact and co-create value with partners in the nonprofit sector that we work with, and deepen those relationships. Through alignment of our business interests and our giving priorities, we will apply Bridgestone’s company ethos— to serve society with quality products, services, and solutions in the mobility space—to the work of creating meaningful change in society.

Specifically, Bridgestone is especially interested in increasing the number of women in the auto tech workforce, which right now is abysmally low. We see supporting organizations such as Play Like a Girl and TechForce Foundation as a means of narrowing this gap.

We’ve started partnership discussions with Play Like A Girl, which in the last twenty years has encouraged girls to be more involved in team sports as a means to engage them in STEM activities and prepare for executive careers, including at corporations such as Bridgestone. This is an organization that focuses on not only young girls, confidence, and mental health, but also diversity in team sports, the classroom, and C-Suite offices throughout the country. We’ll be working with them to enroll girls in Nashville and the Cleveland area (where we have another corporate presence) in mentorship circles with Bridgestone teammates. Likewise, Bridgestone is working with TechForce Foundation, a nonprofit committed to the career exploration and workforce development of professional technicians, on closing the gender gap in the autotech workforce.

Lessons from–and Advice for—the Nonprofit Sector

JL: Tell us about your background in healthy equity and nonprofits and some of the strengths and insights that you feel you bring to the world of corporate philanthropy? How do you think your experiences shaped your conceptions of philanthropy?

WM: I think philanthropy is extremely limited in its ability to address our healthcare system. However, it can be a catalyst for what I think most solutions to our greatest social problems are, which is greater government involvement. Big government, when effective, can achieve significant impact. My own family history is an example of this; when the federal government intervened to bring electricity to the Tennessee Valley, many people were lifted out of poverty.

I think inasmuch as corporate philanthropy can be involved and build relationships with organizations that are engaged in health equity, they can and should also support advocacy work and not shy away from what the actual solutions are, which is that we can’t keep making this piecemeal approach that is doing nothing to really cut costs on our public systems or for individuals. Ultimately we need to find a government solution that is going to be fair and equitable to everyone involved.

JL: What is a piece of advice you can give to nonprofits seeking institutional funding from a corporate partner like Bridgestone ?

WM: Know your value and that your time is just as valuable as a corporate funder’s time, and it’s not worth trying to change your program to fit the corporate interests, because we do have a corporate interest. We do want to move our business forward, and if that is going to hinder your work as a nonprofit, if that’s going to drain your time as a leader in a nonprofit, then don’t do it. It will be much better to find another partner.

WM: Know your value and that your time is just as valuable as a corporate funder’s time, and it’s not worth trying to change your program to fit the corporate interests, because we do have a corporate interest. We do want to move our business forward, and if that is going to hinder your work as a nonprofit, if that’s going to drain your time as a leader in a nonprofit, then don’t do it. It will be much better to find another partner.

I think as a fundraiser you often look at the field of foundations and you look at their assets, and you think, “ohh this organization has X amount of money, they can definitely spare some money for us.”

But with corporate giving, and many foundations, funding determinations are often driven by answers to questions like, “Where are we contextually relevant? Where do we have expertise and experience?” For instance at Bridgestone, we have scientists and researchers. We have an environment and health department. We’ve got a legal department, and so all these areas where we have valuable experience should be leveraged to further our grantmaking. We’re not just giving money, but we’re also leveraging our talent and skills to go that much further, which means that we can’t give to everyone, but instead we give in a way that is going to leverage our resources. And I think that’s going to make for a better relationship with our nonprofit partners.

Implementing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Initiatives

JL: What has centering DEI in your career looked like?

WM: At The Addis Clinic, we worked with state departments and other organizations to deliver telemedicine services in underserved areas in East Africa, refugee camps, and other areas where primary care was not readily available. I was a white male providing direct services to refugee communities. While I recognized that my white privilege conferred certain advantages when it came to fundraising and other aspects of the executive director role, I felt the responsibility to create opportunities for others to lead. As a result, I worked to create a succession plan so that I would be co-director alongside a female healthcare provider.

Prior to the Addis Clinic, I was at Tennessee Justice for Our Neighbors, which provided legal assistance to people seeking asylum and other humanitarian forms of legal relief, and supported victims of violent crimes who needed mental health services and trauma counseling. There, we observed a gross inequity in the number of people of color who were judges and lawyers. In response, we created a six-week summer program to give young BIPOC college students access to judges and lawyers as mentors. We admitted students to the summer program by taking the inverse of what law school currently looks like, which is approximately 3% Latino, 10% African American, and 30% women. It was a refreshing way of looking at entrenched systems of society. I would like to see that in more areas of my work going forward.

Now at Bridgestone Americas, I inherited the current committee that manages the trust fund. Fortunately our leaders were really thoughtful about the composition of the committee, but I think there’s still some work to do in terms of diversity. We want to articulate our commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion through a simple statement of our values and principles. We want to encourage participation from the next generation of leaders at the company, include more voices from underrepresented groups within the company, and be champions for our employee resource groups. We are democratizing grantmaking within the company through employee matching gifts and empowering employee resource groups to provide unrestricted operating grants to nonprofits.

You can learn more about the Bridgestone Americas Trust Fund here. If you found this conversation thought-provoking, keep your eye on this space for new Elevate Q&As in the coming months.

At Elevate, we’ve been thinking a lot this year about Artificial Intelligence (AI) and how it could influence the way that we perform our work supporting nonprofits in building more sustainable grants programs. AI is increasingly relevant in everyday business operations across numerous industries, and it has been applied for many years in ways that many people don’t realize – mapping apps like Google Maps, voice assistants like Alexa and Siri, even the autocorrect feature in your texting app or word processing software are powered by artificial intelligence.

Some interesting trends have emerged in 2023, which hint at AI’s potential while also raising significant ethical and information security considerations. A recent Forbes Advisor survey reports that:

- ChatGPT, an AI powered large language model, had 1 million users within the first five days of being available.

- 54% of survey respondents believe that AI tools like ChatGPT can improve written content by enhancing text quality, creativity, and efficiency in various content creation contexts.

- AI is expected to see an annual growth rate of 37.3% between now and 2030.

- The majority of consumers are concerned about business use of AI.

Accordingly, Elevate is treading optimistically – yet cautiously – when it comes to AI! While we are exploring how AI can create efficiencies in our work, we are also committed to maintaining the highest quality and privacy standards for our clients.

I recently spoke with a handful of my most forward-thinking and tech-savvy Elevate colleagues, who offered their thoughts on what AI applications are and aren’t helpful in aspects of their work advising nonprofit clients. We share their insights here for your consideration as we all navigate this brave new world.

Because many of the questions Elevate receives about AI are about ChatGPT specifically, we begin with the 411 on this tool.

Even if you haven’t yet used it yourself, you’ve undoubtedly heard the buzz about ChatGPT. ChatGPT is a free, natural language processing tool that can answer questions and support users with tasks such as composing emails, essays, and code. It can spew out responses in a matter of seconds. It does this by analyzing your question or prompt, then – using the dataset it was trained on – predicting the next word or series of words based on what you’ve entered.

But is it savvy enough to write sophisticated, nuanced, and winning grants?

Our colleagues were unequivocal in their response: Not even close.

This is because ChatGPT lacks the context, experience and judgment to handle such complex work. Even when I asked ChatGPT “What are the Pros and Cons of Using ChatGPT for grant writing?” it didn’t disagree! While ChatGPT praised its speed and ability to maintain consistency in “tone, language, and messaging” across various sections of a grant proposal and to polish language, it cautioned that it may not fully appreciate the “nuances” of grant guidelines, that it has limitations in understanding the context of an organization’s work and history, and that it could also produce plagiarizing text.

This is because ChatGPT lacks the context, experience and judgment to handle such complex work. Even when I asked ChatGPT “What are the Pros and Cons of Using ChatGPT for grant writing?” it didn’t disagree! While ChatGPT praised its speed and ability to maintain consistency in “tone, language, and messaging” across various sections of a grant proposal and to polish language, it cautioned that it may not fully appreciate the “nuances” of grant guidelines, that it has limitations in understanding the context of an organization’s work and history, and that it could also produce plagiarizing text.

The text that ChatGPT generates in response to a question or prompt might not even be factual – there are absolutely no assurances that the information is accurate or true.

What’s more, because ChatGPT and other AI models draw upon existing content, AI can reflect underlying societal biases, perpetuating stereotypes and white supremacist notions. At Elevate, we know that historically marginalized communities are not “vulnerable” objects of charity, but agents and partners of the social change that they desire to see. This level of social context is far too complex for an AI-powered language model to appropriately reflect.

So, what are the appropriate uses of ChatGPT?

If you do want to experiment with ChatGPT in your writing tasks, we suggest using it for simpler, less analytical tasks, such as condensing word count, identifying alternative phrasing to avoid repetition, or summarizing the main points of your research into more readable language.

ChatGPT also has the potential to provide administrative support for your work, and can be harnessed to:

- Organize a to-do list

- Summarize meeting minutes

- Brainstorm ideas

But whatever you do, do NOT rely on ChatGPT to produce your next grant proposal.

I know what you are thinking: It’s no surprise that a grant writing firm is telling me not to use an AI tool to write grants! But we are not just saying this because we want to be your grant writers. (Though we DO want to be your grant writers!)

I know what you are thinking: It’s no surprise that a grant writing firm is telling me not to use an AI tool to write grants! But we are not just saying this because we want to be your grant writers. (Though we DO want to be your grant writers!)

At Elevate, we firmly believe that good grant writing is a thoughtful, strategic exercise that requires skill, nuance, and informed decision making. ChatGPT – like other AI tools – is neither thoughtful nor strategic. It lacks discernment of nuance, and is incapable of making reasoned choices about how to present an organization’s work to a funding partner.

Simply producing large volumes of content – that may or may not be factual! – is NOT the point of grant writing. And this is truly all that ChatGPT is doing: generating text.

AI Tools CAN Help You Take Notes, Summarize Content, and Find Information

At Elevate, some of our staff are experimenting with the use of AI-powered tools such as Simon Says AI and Fathom Notetaker to capture meeting notes and provide summaries of important conversations that they need to refer back to later or share with colleagues who couldn’t attend meetings. By using AI tools for more administrative tasks, you can free up some of your own time and energy for tasks that require thought and strategy – something AI can’t do!